This is the first of a two part series about the work of scientists and volunteers who are fighting a coral disease that is ravaging Virgin Islands reefs.

Anyone who knows Jeff Miller, a fisheries biologist with the National Park Service based on St. John, knows him to be methodical, cool-headed and analytical.

So when Miller showed up for a practice swim for a Virgin Islands National Park fundraiser last Sunday, the alarm in his eyes and the urgency in his voice were definite signs of trouble.

“I’ve been off island for four weeks,” he said. “I just got back and did a swim at Maho Bay Point. The bad coral disease has now made its way along the most popular spots on the north shore, including Trunk Bay, Cinnamon Bay, Francis Bay and Waterlemon Cay.”

Miller was referring to Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease, commonly known as SCTLD (pronounced “skittled”), which was first spotted at a cay off St. Thomas in January 2019 and has now spread throughout the Virgin Islands. The disease has been decimating 22 of the 40 local species of corals, many of which are the building blocks of Virgin Islands coral reefs.

Miller did not mince words. “The bottom line is if visitors or locals want to see brain corals and pillar corals, they have only a few weeks left,” he said. “Take your kids to see them now. Take photographs. Don’t wait. There is a very short window of opportunity to see the reefs in all of their magnificence.”

Miller equates the spread of the disease to a forest fire ravaging the marine landscape. “I believe this disease will have a greater impact than hurricanes Irma and Maria combined,” he said. “If people smelled the smoke and it burned their eyes, there would be a larger response, but it’s going on out of their sight. “

His warning is dire, but a dedicated corps of researchers, divers and community partners are not giving in to Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease without a battle.

Joe Townsend, the territory’s coral disease response coordinator, is leading an effort that includes the scientists, technicians, students and volunteers with the National Park Service, the Department of Planning and Natural Resources, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The University of the Virgin Islands, Nature Conservancy, Caribbean Oceanic Restoration and Education Foundation and Coral World Ocean Park. Agencies within the territory are partnering with agencies in Puerto Rico, the British Virgin Islands and the United States.

“We are in the process of building our capacity for coral rescue. Some of our most vulnerable corals have been around for hundreds of years, yet they’re dying in a matter of weeks. We can bring them to our restoration facilities, heal them, and regrow them,” Townsend said.

Researchers develop techniques for growing coral in nurseries.

One of the leading proponents of coral restoration is Dr. David Vaughan, an aquaculturist with decades of experience in coral restoration research. He served as the director of Mote Marine Laboratory’s Elizabeth Moore’s International Center for Coral Reef Research and Restoration, which has pioneered critical restoration techniques now used in multiple locations.

Two years ago, Vaughan retired and started his foundation called Plant a Million Corals, an initiative to distribute complete, small-scale coral nurseries throughout the Caribbean.

Many Virgin Islands residents learned about Vaughan’s work when he made the keynote presentation at the Friends of the Virgin Islands National Park’s annual meeting held online in January. His presentation can be heard here. (His session begins about 70 minutes into the recording.)

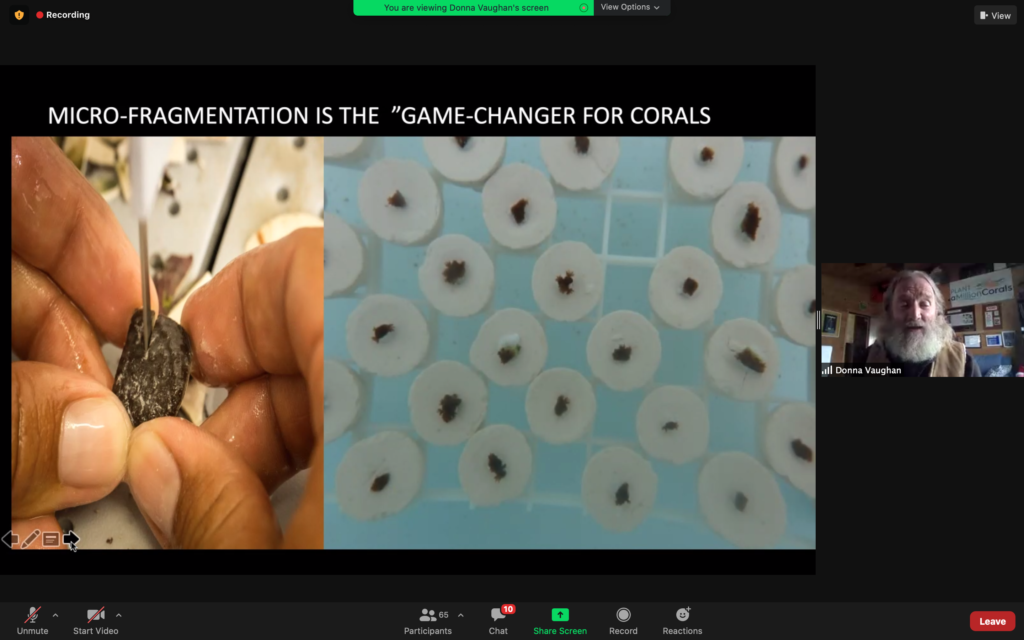

At that meeting, Vaughan described his work growing corals through a method called microfragmentation, which he characterizes as a “game-changer.” The technique was first found to work on fast-growing branching corals, such as staghorn and elkhorn corals. It has now been shown to work on the slow-growing stony corals which are being destroyed by SCTLD.

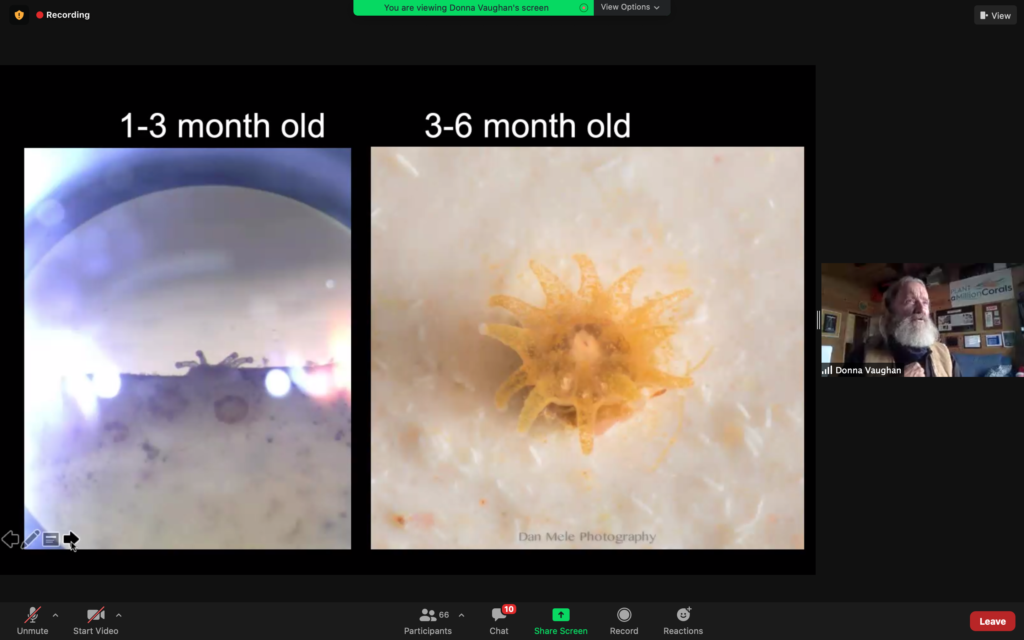

The technique involves using a specialized bandsaw blade to cut coral into tiny pieces. “If coral is broken, it has the ability to repair itself at record speed, like we can heal a cut on our skin quickly,” Vaughan said.

Vaughan starts with a golf-ball-size piece of coral which he cuts into dozens of pieces; he then attaches each piece to a small ceramic plate and places them in tanks of seawater.

“The coral fragments grow back in size within a matter of weeks instead of years,” he said. “It’s a simple technique that can be taught to students and volunteers. You can grow a million corals within one year if you have the staff and the facilities.”

Vaughan made another important discovery. “Normally, we don’t like to put corals near each other. They don’t like to touch each other. They will literally fight,” he said. In the lab, however, researchers didn’t have the luxury of giving each of the growing corals a lot of space. Then when corals within the same row started touching each other and fused together instead of fighting, researchers were shocked.

Vaughan calls this process “reskinning” and attributes it to the fact that all the corals come from the same parental piece. “They recognize their tissues as themselves.”

Once they’re replanted in the water, the corals grow more slowly, but the microfragmentation technique gives the corals a critical boost at an early stage of their lifecycle. Within two decades, some replanted corals have served as the bases of reefs which continue to flourish and attract a variety of marine creatures.

Vaughan has developed a self-contained lab and “nursery in a box” – a shipping container that includes all the pipes, tanks, filters, pumps and equipment to grow coral for about $100,000. Staffing costs are additional. Several local organizations are now considering purchasing one of these units.

Vaughan’s is not the only system now being used to grow coral. According to The Nature Conservancy’s website, “For the first time in the Virgin Islands, The Nature Conservancy and partner SECORE International conducted a successful coral spawning expedition and used groundbreaking sexual reproduction techniques to grow healthy baby corals. The expedition was part of the TNC’s coral conservation initiative to restore reefs across the Caribbean by using cutting-edge science to grow and outplant at scales never before possible.”

The University of the Virgin Islands and Coral World Ocean Park has also been collaborating to treat endangered corals. Dr. Marilyn Brandt, the UVI researcher who first spotted the outbreak of SCTLD in the USVI in 2019, heads up this initiative.

UVI is now offering a summer program to involve young people in the fight to save corals.

Up next in this series: Strike Teams fight coral disease underwater