The following story is part of a series highlighting individuals’ experiences with systemic racism on the U.S. mainland. Some of the stories have focused on Black men and women who grew up in predominantly Black communities in the Caribbean. The following are stories of Black people who were born on the mainland and later established roots in the Virgin Islands.

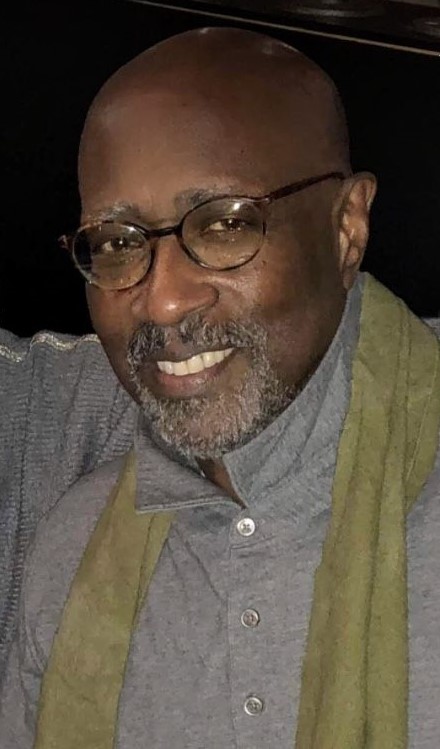

George Marshall Miller was born in New York City to Caribbean parents and grew up in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood. Bed-Stuy, as it is known colloquially, was 95 percent Black, Miller says.

The first time he remembers seeing white people – other than his maternal grandmother – was when “two white men brought oxygen tanks up four flights of stairs” to where his father was dying of lung cancer.

He was 3 years old. “They were strange looking guys,” but he didn’t think about them being “white.” “They may as well have been purple,” he says. “As a kid you see all these variations, but they don’t have any significance.”

“Race is something we learn.”

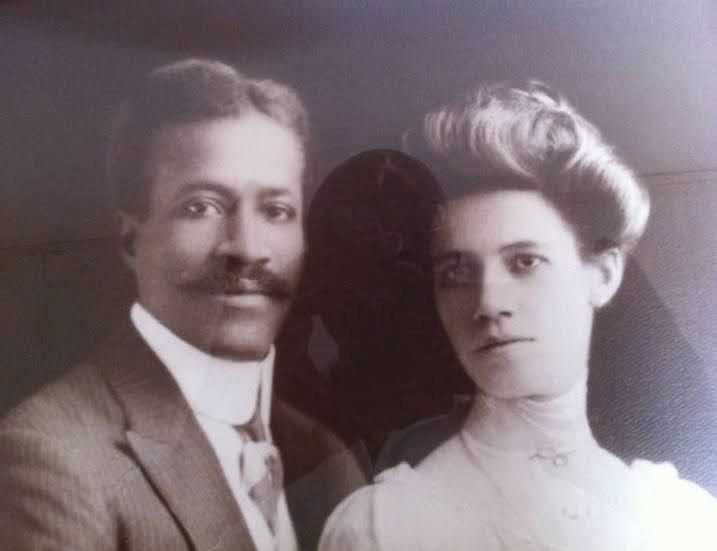

Miller said his most vivid awareness of racism comes from family stories. Miller’s grandfather was “my color,” he says, and his grandmother was 95 percent white. They both came from Barbados.

He remembers being told one story over and over. “I was in Tompkins Avenue Park with my grandmother. I was maybe 5,” the story goes. “A white woman walked up to [my grandmother] and asked, ‘Is that little boy bothering you?’”

“No,” my grandmother replied. “He’s my grandson.”

But to Miller, these were still just stories. “No one sat me down and explained these things.”

He admits to being deeply touched recently by John Lewis’ remark in the essay the deceased congressman wrote just days before his recent death. Choking up, Miller repeats Lewis’ words, “Emmett Till was my George Floyd.”

Miller, wiping tears from his cheeks says, “I was 9 when the Emmett Till thing happened. Our whole family was upset. Our whole neighborhood was upset.” His block in Bed-Stuy included mostly people from Barbados. “The South was remote to us.”

Another family incident happened before Miller was born, when his mother moved from New York to Washington, D.C., during World War II to work for the Signal Corp., which was part of the then-War Department, now Department of Defense.

Her mother, Miller’s white-skinned grandmother, traveled from New York to segregated D.C. to visit her daughter. The tale is of a city bus trip during which Miller’s mother was forced to sit in the back of the bus, while her mother sat in the front.

In another public transportation family saga, Miller’s grandparents were sitting together on a streetcar in Manhattan when a white man got on board. Because all the seats were filled, the conductor told Miller’s Black grandfather to get up from his seat next to his white wife so the white man could sit down. “No, I won’t do that,” said his grandfather, so the legend goes. A standoff – it doesn’t end with violence, nor with his grandfather giving up his seat.

But those were not the only situations or incidents in his childhood that Miller now sees were racist or divisive.

“Even in our family there was colorism,” he remembers. “People were complimented for having light skin and good hair,” – straight hair. Miller was dark-skinned and nappy haired.

And in his all-Black neighborhood, when a report of a criminal incident made its way around the block, the question inevitably was, “Were they Black or white?”

He says, “You begin to realize it matters what color you are.”

As the ‘60s were birthed with their attendant civil rights demonstrations, riots and emerging Black Power movement, Miller himself began to connect with the reality of America’s racism. On the up side, his nappy hair was suddenly “in.”

Miller grew up attending an all-Black Catholic elementary school where he was taught by white nuns, and it was the parish church affiliated with that school that arranged to take a busload of parishioners to the 1963 March on Washington.

Miller and his sister wanted to go. “My mother was against it.” She was afraid. But eventually, she relented, and Miller and his sister boarded that bus and were on the Washington Mall with another 250,000 people on Aug. 28, 1963, when Martin Luther King Jr. gave his most famous speech.

Five years later Miller would be arrested on his Columbia University campus and jailed, along with hundreds of other students, for participating in student demonstrations after King’s assassination.

He recalls each police officer was assigned to arrest two demonstrators.

While the cops’ attire and accouterments – black leather boots and jackets, riot clubs and guns – was intimidating, in the end, Miller became aware that despite the 6 feet, 3 inches, 200-plus pound bulk of the cop who handcuffed him, “me and my buddy, he was also afraid of us.”

Miller, a lawyer and yoga practitioner, laughs at the thought of the police being afraid of him.

“It was around sunset when we were arrested. We weren’t put in a cell until 2 a.m.” In the time between, “we became friends.” At some point, the officer removed their handcuffs and offered them cigarettes and gum as they talked for hours. “We were just like three guys.”

Once in the cell, however, they met with a much more aggressive cop who demanded their shoelaces and belts, “like I was going to hang myself over a misdemeanor,” Miller laughs at the memory.

Between the Washington march and Columbia arrest, Miller’s history also includes attending the funeral of Malcolm X in Harlem.

While it was a momentous time to be alive in America, Miller – with his Barbadian heritage – was always curious about his Caribbean roots. Upon his graduation from college in 1967, his mother treated him to a long trip through the Caribbean islands. Barbados, of course, Puerto Rico, Jamaica and St. Thomas/St. John. “In Barbados, I saw places I had heard about all my life.” Back in New York, he told his friends, “the Caribbean is where I want to live.” He returned to visit the Caribbean in 1969, and again in 1971 after graduating from Columbia Law School. He says he was attracted to the V.I. because it was a predominantly Black community, “Black governor, mostly Black legislature and police force, as well as a potential place of employment for someone with an American law degree.”

A year later, seven white men were killed on St. Croix in what became known as the “Fountain Valley Massacre.” A Black Crucian man was also gunned down.

Soon thereafter there was an exodus from the local attorney general’s office of most of the white lawyers, including the then-attorney general himself, Ronald Tonkin.

Verne Hodge, who later became chief judge of the then-U.S. Virgin Islands Territorial Court, was appointed attorney general and began to recruit lawyers to fill the vacancies.

Three years, and one interview in Washington, D.C., with then-first Attorney General Henry Feuerzeig later, Miller moved with his wife and two sons to St. Thomas, where he has been for the last 47 years.

“St. Thomas has changed,” he says, “It’s congested.”

He remembers a time when no one locked their doors, there was no gun violence and people were not afraid to go out at night.

He attributes the increasingly violent behavior to what B.F. Skinner discovered in his rat experiments – the more rats you put in a cage together, the more aggressive and anti-social they became.

But, Miller says, “I’m still here.”

Patrice Johnson says she was “a protected child.” Growing up in East Elmhurst, New York, in what was one of the first neighborhoods where Blacks were able to buy homes in the ‘60s, put her in a cocoon of sorts. “We were the second wave of homeowners,” she recalls. “The first were Italian Americans.” Her mother was a federal employee and her dad a unionized transit worker.

We were lower-middle class, but “We had a backyard and a driveway.”

She could walk to PS 125 from her home. The school at the time was mixed, though more Black than white, she says, until the white kids from Jackson Heights were bussed in.

The white kids were mostly Jewish children of post-Holocaust progressives. “We learned from one another.” Being children of the mid-‘60s Civil Rights Movement, “We were all very connected.”

Even though the arrival of the white kids shifted the racial mix, leaving Johnson one of only two Black kids in her class, racism was not, nor did it become for many years, a reality for her.

She does have a vague memory of an incident at a Howard Johnson’s on the New Jersey Turnpike. “We were on a family trip and stopped to get something to eat.”

She said as time passed without anyone approaching the table to take their orders her father became more and more agitated. “Finally, we left,” she says, adding “I was never sure that’s what it was [that they were Black], but my father decided that’s what it was.” She remembers him saying, “From now on we pack our lunch.”

Johnson also remembers her parents were big “Martin Luther King fans.” She says they shared his values. But Malcolm X loomed large in her life. He lived four blocks away on East Elmhurst’s 97th Street, the Johnsons on 100th. It was the house that would be bombed in February 1965, one week before Malcolm X was assassinated.

“My parents … firmly believed he was a radical.” Johnson says she does understand why her parents were so troubled by his ideas.

She, on the other hand, became fascinated. “Seeing Malcolm X’s children [wearing hijabs] who were the same age as me, made me curious.”

Johnson says they had a way of carrying themselves that suggested “they knew who they were.” She mused these children of Malcolm X were being taught something at home that she wanted to know more about, which was related to the Nation of Islam.

She read everything she could about the movement, which may have drawn the movement closer to her door. She says one Sunday, she glanced out the living room window to see two men in suits walking by. “It was Malcolm X walking down the street with Muhammad Ali.”

Ali changing his name and giving up the world heavyweight crown due to his beliefs about the Vietnam War also piqued her curiosity.

In her family, Ali was seen as a draft dodger more than the hero many in the younger generation felt he was for his courage and stunning losses as a result of his convictions.

With all of that – the bombings, protests, assassinations, movements – Johnson herself remained in a bubble, one that saw her through college at Hampton University, a Historically Black University in Washington, D.C. Being there was “comforting,” she says, “like having my own yeshiva.”

Four years later, however, she found herself back in New York City – a minority female – with no mentor and “no clue how to get someone to give me a leg up.” The bubble was thinning.

She still thought it was somehow her fault that, even with her bachelor’s degree, the best she could do was land one secretarial position after another. “I chalked it up to ‘I didn’t try hard enough.’”

She also chastised herself for choosing to stay in New York – a, if not the, prime job market in America.

She kept thinking she might do better in a small town. “But I chose to stay.” For many years she felt like it was taking her “forever” with just her bachelor’s degree “to get someone to realize I had a brain.”

She did a brief stint in 1978 with a Public Broadcasting station in D.C., but it was still a secretarial position. “Even though I could edit tape for broadcast and write.”

“I was naive. I didn’t chalk it up to racism.”

Later, Johnson landed in Westchester, New York, where after a brief turn as the obit clerk at the Gannett-owned paper there, she made the decision to enroll in Columbia University School of Journalism.

After graduating in 1991 she took a job in Stamford, Connecticut, as a general assignment reporter with the Stamford Advocate, covering things such as town hall meetings.

By now, the bubble had burst; she was a credentialed Black woman reporter in a white community who was questioned when she tried to cross police lines at crime scenes. “I was the one who would get stopped.”

It was a struggle to get people to engage with her when she was on the job, reporting. “It was hard to get them to open up.”

She longed for something more. A place where “people would speak with me.”

In 1996, she found her way “home” to the Virgin Islands, when she was hired by The Daily News, at the time also a Gannett publication.

The Virgin Islands is where she says she found peace, was given value and appreciation.

From the moment she arrived, she says she felt “completely at home.” The door was finally opened for her to prove herself. She had found a place where she was part of a racial majority.

The Virgin Islands is where her daughter was born and raised.

“This is our home, and I am glad for it. This is where I belong.”